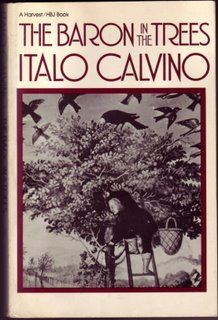

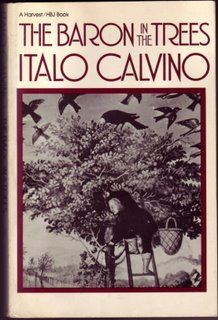

Just finished Calvino's Baron in the Trees. Not a great novel, but Calvino has a knack for taking a simple but unusual idea and running with it. The main character, Cosimo, initially decides to climb into the trees after being scolded by his parents. He resolves to stay in the trees initially to spite his parents and win a challenge with a neighboring girl. His reason for climbing into the trees dissolves as he becomes preoccupied with the strategies for living above ground. His freedom, independence, and ingenuity in finding ways to survive brings him into adulthood and forms his identity. Staying in the trees, keeps him from trespassing on other nobles' land and represents uncharted territory for him to claim and explore. The charm of the novel is in taking an idea as simple as a child's rebellion and mixing it with a will that allows the consequences of a creative act to unfold. How many kids have fantasies about faking their own funeral in getting back at their parents (and won't they be sad then!)? By the next morning in the life of the average kid, everything is back to normal. Cosmos will to stay aloft doesn't stem from the passion or ability to hold a grudge, but stems more from the desire and sense of expectation in autonomy and the possibilities of a creative act. For Cosimo, the life of living in the trees offers a path to exploring and discovering the world from a new vantage point. He achieves status and finds ways to interact with the community around him without compromising his pact to live apart from that community. It is easy to associate Cosimo's decision to live in the trees with a chosen life path of the bohemian/artist/writer/philosopher. Calvino adds a sense of the enjoyment of creativity in Cosimo discovering how to maintain essential comforts and necessities of life in his new world. Food, heat, shelter, bathing, travel, sex, relieving oneself, cooking, and engineering all have to be figured out anew by the lead character in the story.

One becomes less interested in the life as the novel tries to close. The destination of a walk is seldom at its end. This holds true for Calvino. The general glee Calvino's absurd scenarios give us are gems in themselves and don't always need 200 hundred pages to reveal their worth. Like Kafka and Borges, the drawing out of a story can sometimes dull the sparkle and charm of Calvino's ideas. Kafka could give a sense of monotony in 6 pages as well as a hundred. Calvino can involve you in a story within a couple of paragraphs. The short below is from Calvino's Numbers in the Dark.

The Man Who Shouted Teresa

by Italo Calvino

"I stepped off the pavement, walked backwards a few paces looking up, and, from the middle of the street, brought my hands to my mouth to make a megaphone, and shouted toward the top stories of the block: "Teresa!"

My shadow took fright at the moon and huddled at my feet. Someone walked by. Again I shouted: "Teresa!" The man came up to me and said: "If you do not shout louder she will not hear you. Let's both try. So: count to three, on three we shout together." And he said: "One, two, three." And we both yelled,

"Tereeeesaaa!"

A small group of friends passing by on their way back from the theater or the cafà saw us calling out. They said: "Come on, we will give you a shout too." And they joined us in the middle of the street and the first man said one to three and then everybody together shouted,

"Te-reee-saaa!"

Somebody else came by and joined us; a quarter of an hour later there were a whole bunch of us, twenty almost. And every now and then somebody new came along.

Organizing ourselves to give a good shout, all at the same time, was not easy. There was always someone who began before three or who went on too long, but in the end we were managing something fairly efficient. We agreed that the "Te" should be shouted low and long, the "re" high and long, the "sa" low and short. It sounded fine. Just a squabble every now and then when someone was off.We were beginning to get it right when somebody, who, if his voice was anything to go by, must have had a very freckled face, asked:

"But are you sure she is home?"

"No," I said.

"That is bad," another said. "Forgotten your key, have you?"

"Actually," I said, "I have my key."

"So," they asked, "why dont you go on up?"

"I don't live here," I answered. "I live on the other side of town."

"Well, then, excuse my curiosity," the one with the freckled voice asked, "but who lives here?"

"I really wouldn't know," I said. People were a bit upset about this.

"So, could you please explain," somebody with a very toothy voice asked, "why you are down here calling out Teresa."

"As far as I am concerned," I said, "we can call out another name, or try somewhere else if you like."The others were a bit annoyed.

"I hope you were not playing a trick on us," the frecled one asked suspiciously.

"What," I said, resentfully, and I turned to ther others for confirmation of my good faith. The others said nothing.

There was a moment of embarrassment.

"Look," someone said good-naturedly, "why don't we call Teresa one more time, then we go home."

So we did it one more time.

"One two three Teresa!" but it did not come out very well. Then people headed off for home, some one way, some another.

I had already turned into the square when I thought I heard a voice still calling:

"Tee-reee-sa!"

Someone must have stayed on to shout. Someone stubborn.